O’Keefe dishes all the secrets about who’s on the hillsides and who’s on the flats; and for those who would find it fascinating to know who makes wine from Montosoli (probably the second-most esteemed Brunello vineyard after Biondi-Santi’s Il Greppo estate) without bothering to mention it on the label, this is the source.

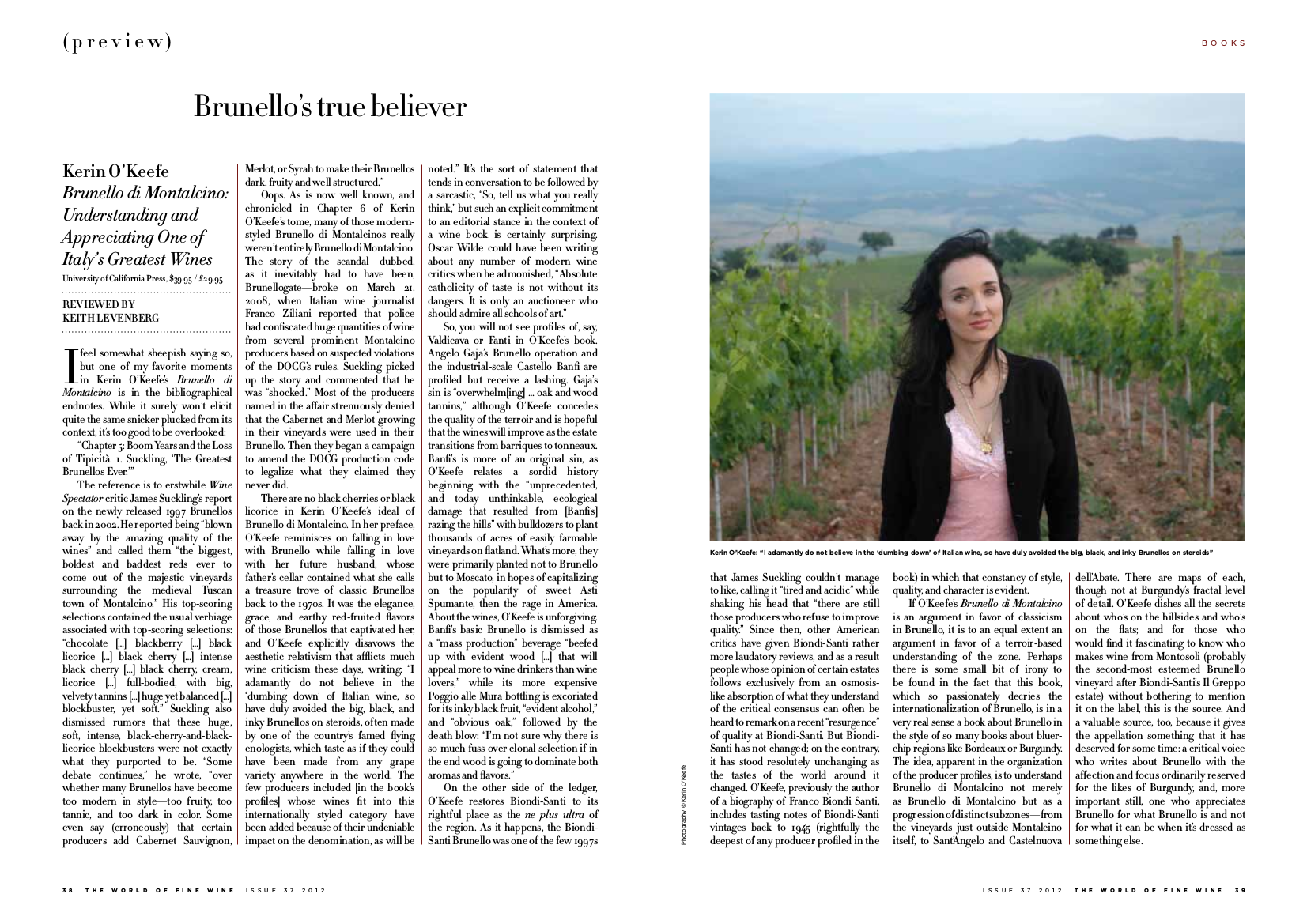

Kerin O’Keefe, Brunello di Montalcino: Understanding and Appreciating One of Italy’s Greatest Wines

And a valuable source, too, because it gives the appellation something that it has deserved for some time: a critical voice who writes about Brunello with the affection and focus ordinarily reserved for the likes of Burgundy, and, more important still, one who appreciates Brunello for what Brunello is and not for what it can be when it’s dressed as something else.

Read the full review: “Brunello true believer”, Review of Kerin O’Keefe Brunello di Montalcino: Understanding and Appreciating One of Italy’s Greatest Wines by Keith Levenberg in The World of Fine Wine (37) 2012

book review Brunello Keith Levenberg Montalcino Sangiovese World of Fine Wine

Last modified: December 20, 2023