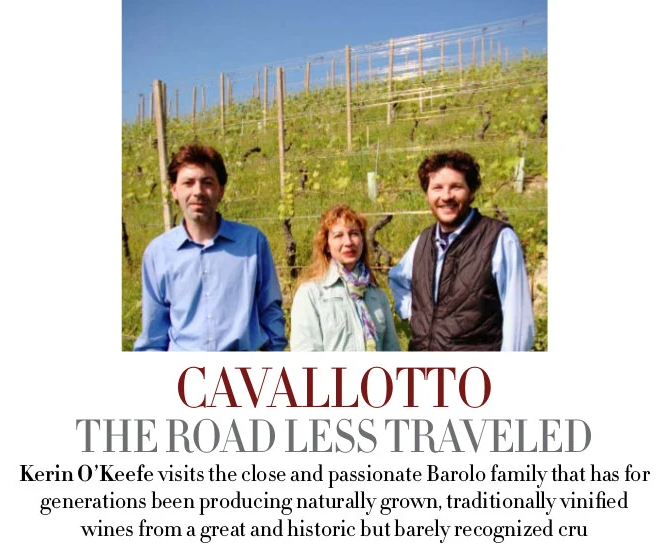

Kerin O’Keefe visits the close and passionate Barolo family that has for generations been producing naturally grown, traditionally vinified wines from a great and historic but barely recognized cru.

Read the article: OKeefe_Cavallotto.pdf

Barolo Castiglione Falletto Cavallotto Nebbiolo World of Fine Wine

Last modified: February 9, 2024