Terroir isn’t just about wine. Chefs in Italy are looking local for their ingredients, from Caffè Cibrèo in Florence to Osteria Disguido in Piedmont.

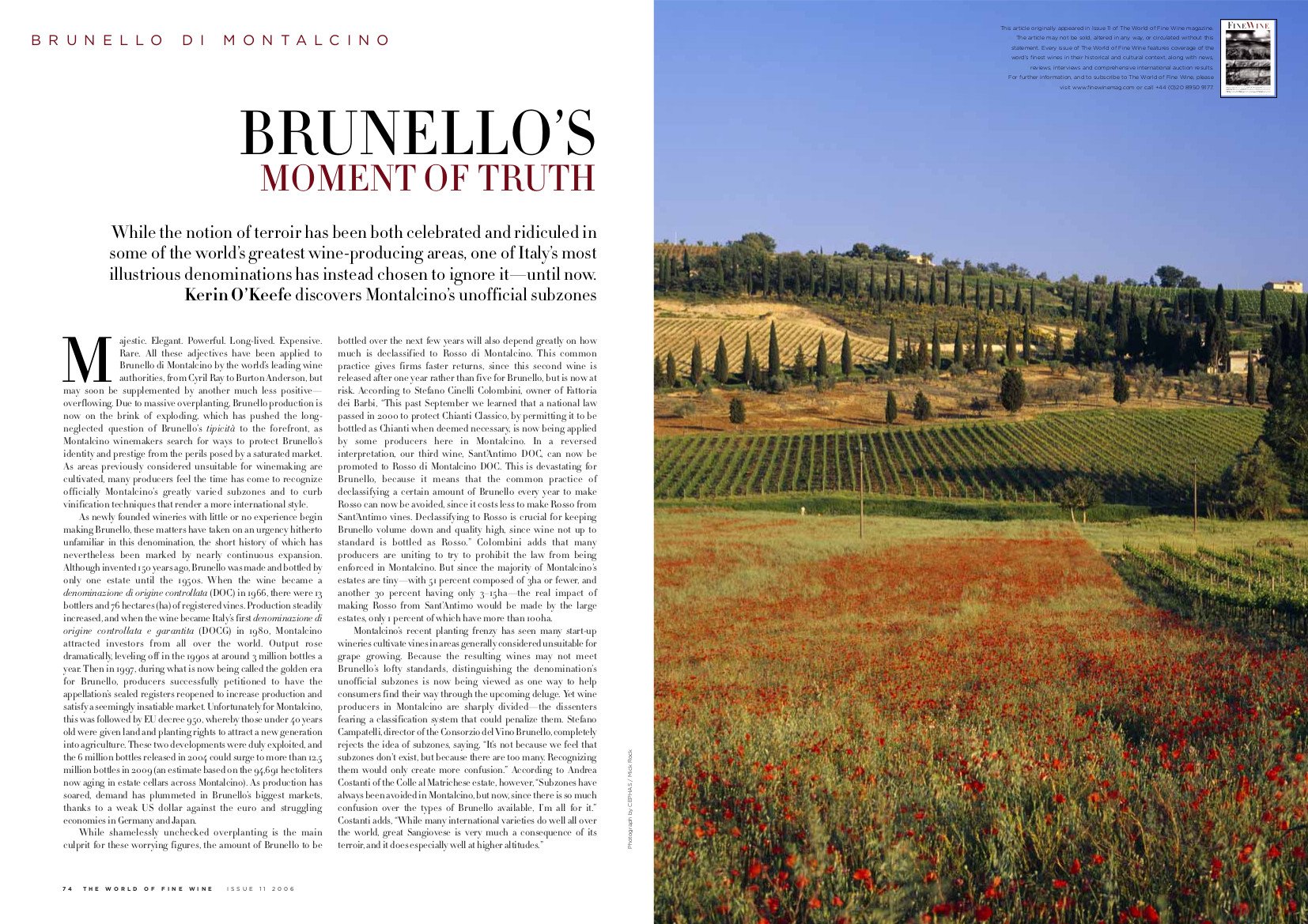

Fabio Picchi in front of his Caffè Cibrèo in Florence

“Terroir-driven wine” has become synonymous with a high-quality product loaded with the personality of the place (or soil) in which it’s made/grown. But in Italy, terroir is also a key concept behind much of the country’s best cuisine.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, winemakers focused efforts on new techniques and cellar technology to improve their wines. Since then, producers have turned their focus to the vineyards. How and where grapes are grown are now seen as the most important factors in quality winemaking.

The same emphasis on terroir can be said for today’s best Italian cuisine. It starts with select ingredients from distinct areas of the country.

Earlier this month, I made my way to Florence. No visit to the Renaissance capital is complete without a stop at one of Fabio Picchi’s three Cibrèo dining establishments.

This time, my companions and I ate at the cozy Caffè Cibrèo, where every ingredient in every dish sang out. Even a sliced heirloom tomato dazzled on its own. It was thick, juicy and savory, sprinkled with fresh basil and drizzled with extra-virgin olive oil. It halted our group in mid-conversation.

Picchi, who spends much of his time sourcing the ingredients for his dishes, explained that the tomato was from the coastal Tuscan town of Donoratico, in the province of Livorno. It’s where, centuries ago, Spanish exiles settled and brought with them tomato seeds from the Americas. Today, a handful of farmers still grow fruit from this ancient clone. Meanwhile, the olive oil comes from the hills around Florence, and the basil was also grown locally.

“The beauty of quality raw material is one of life’s gifts and is enough to make me happy every morning,” says Picchi. “Simplicity is like having pure air for breathing. It’s like music.”

After several more appetizers, including a rare Pertosa white artichoke, our first courses arrived. My pasta, busiate, made with ancient grains from Sicily, was topped with a light tomato-vegetable sauce and was full of flavor. My dinner companions enjoyed their dishes of baccalà and a locally sourced tuna called palmita, caught off the shores of Isola d’Elba.

Picchi served a delicious mineral-driven white (Madonna del Latte Viognier) with our appetizers and first course.

“The beauty of quality raw material is one of life’s gifts and is enough to make me happy every morning. Simplicity is like having pure air for breathing. It’s like music.” —Fabio Picchi

My second course was a lightly fried scamorza, a cheese made from the milk of cows that graze in the open pastures of Sardinia, topped with Porcini mushrooms from the nearby Garfagnana forest. The result was a substantial yet weightless dish.

Picchi explained that the lightness is due in part to the thistle rennet used in the cheese-crafting process, as opposed to animal-derived rennet, making the cheese easier to digest.

Up in Piedmont, one of Italy’s most celebrated cuisine capitals, a “light” lunch last week at Fontanafredda’s Osteria Disguido (the informal counterpart to Ristorante Guido) again proved the importance of fresh, unique ingredients.

Our pasta was made with Italian wheat from Gragnano in Campania, while the selection of cheeses included an exquisitely delicate Robiola di Roccaverano, a soft cheese made from goat’s milk. The goats only eat the grass of their Alta Langa pastures, which imparts seasonality to the cheese.

Dessert was the showstopper: cold, fresh and concentrated cream, sans preservatives or added flavoring, whipped up at the moment. The cream hails from 400 rare Bianca Piemontese cows that graze in high Alpine pastures in the Cuneo province. Fontanafredda’s vibrant 2015 Moscato d’Asti Moncucco made an excellent match

Let’s not forget the chef’s role in terroir-driven cuisine. Just as the best winemakers say that they merely guide the wine in the cellars, the best chefs don’t need to rely on fancy presentations or complicated sauces. Instead, they carefully source only select, seasonal and wholesome ingredients. These offer layers of flavors and texture, which create soul-satisfying meals.

Cibrèo Fabio Picchi Fontanafredda Osteria Disguido Terroir

Last modified: December 31, 2023